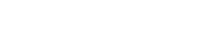

In Deep Sea Aria and its companion world Archive – Deep Sea Aria, Japanese VR world designer and writer Aki Saikawa, and vocal artist Ao Mihanada, produced a moving and defiant multi-platform VR performance blending speculative fiction, poetic monologue, and live music into a story about the limitations of digital existence. Set in two linked VRChat worlds, an exploratory narrative space and a memorial concert venue, this VR “reading drama” project invites participants to piece together the memories of Ao (lit. blue in Japanese), a young woman who uploads her consciousness to an electronic city called Deep Sea. The price for this service is that she must leave her physical body behind.

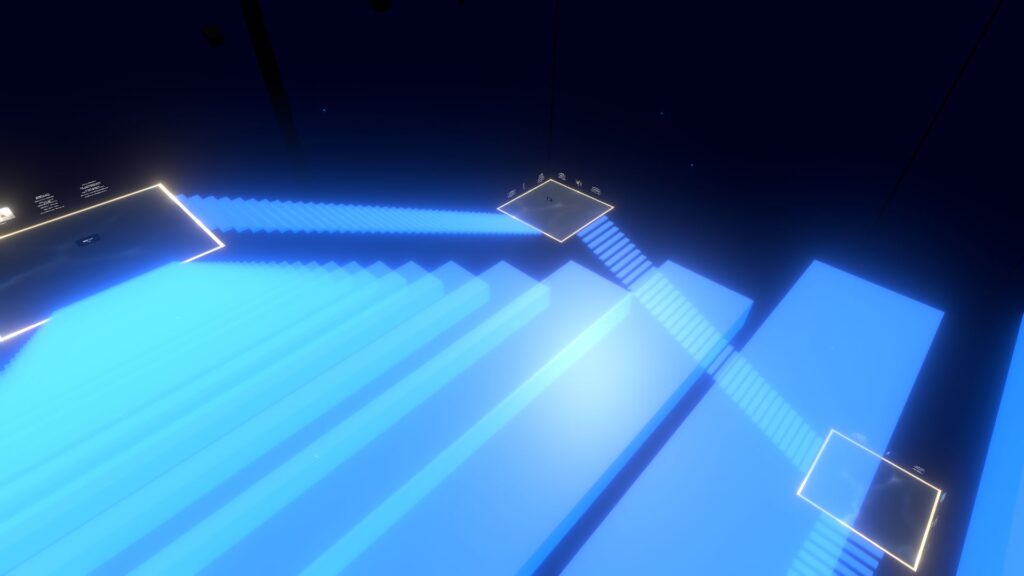

The performance culminates in Ao’s final three concerts, spread over three days. Each event brings her closer to being “deleted” by the authorities of Deep Sea. Three live performances by Vsinger Ao Mihanada were held in the Deep Sea concert venue from June 19-21 2025 in VRChat. The worlds for these live shows are currently open to the public (July 18-31 2025), and recordings of Mihanada’s performances are accessible in the “Archive” world. This review is based on my experience of the archival version of the project.

World design as dramaturgy

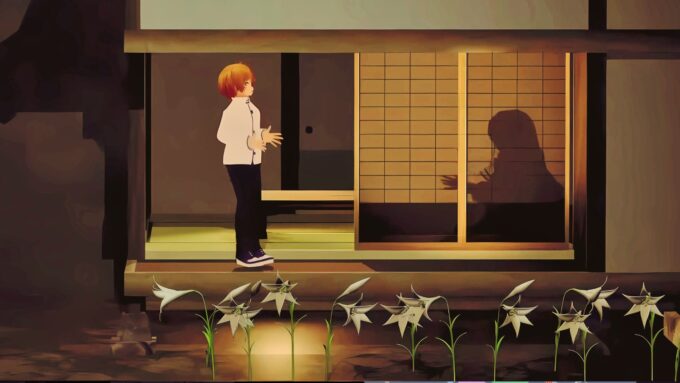

This virtual experience, set in 2225, begins in the Deep Sea Aria world, an electronic dreamscape composed of ethereal blue staircases and floating platforms submerged in an ambient, oceanic void. As audiences descend these layered stages, they encounter text fragments, images, and voiceovers from the protagonist Ao, who chronicles her journey to Deep Sea, driven by the desire for a release from human suffering.

Designed as a solo audience experience (though it is possible to view it as a group), the fragmented structure of Deep Sea Aria reflects Ao’s own state of mind. Audiences progress through each level at their own pace, using buttons to activate voiceovers and cross thresholds. Each platform functions as a memory node in a network of digital introspection. The world’s silence and minimalist interaction design heightens the sense of intimacy and involvement in Ao’s story, but it is also alienating, slow, frustrating, and solitary. This too, is an echo of Ao’s own isolation.

The second VR world: Archive – Deep Sea Aria is a stark contrast. Ao appears as a glitching hologram standing on a concert stage, at the foot of the towering spires in the Deep Sea city skyline. This space serves both as the site of her final rebellion, a live concert which we are told is forbidden in this electronic society, and as a lasting memorial, allowing participants to replay her final song performances and speeches. Together, these connected worlds create a dramaturgy of immersion and reflection, exploration and witnessing, a performance that unfolds in shards of digital memory.

Rebirth as resistance

At the core of Ao’s story is an unexpected twist. The posthuman narrative of mind uploading; of leaving the human body to join a technological singularity, is well-worn science fiction trope. Richard K. Morgan’s 2002 cyberpunk novel, Altered Carbon, is a key reference point in this subgenre. It stages the digital afterlife as class struggle, where only those who are willing and able to pay get a chance at fending off finitude. It also presents digital consciousness as a holistic data set that can be stored and replayed at any given time. Deep Sea Aria, on the other hand, places the onus on a speculative trade-off in the transition to digital subjectivity. The price for Ao’s ticket to digital consciousness is not just to abandon her body, but also to lose access to her memories. That’s not all though. The electronic city (Deep Sea) that she has bought into is a highly regulated, technocracy in which stability and stasis are the law, and emotion, creativity, and individual expression are deemed transgressive.

Ao embarks on this transformation to be released from pain and suffering. However, it is not clear what the cause of her pain actually is. There is mention of childhood parental neglect, and the sudden loss of a loved one, but all this is told in passing. As a result, we are left with a loose thread. If Ao is aware that entering the digital realm can lead to even greater suffering than her current state, why make the transition? In any case, after entering Deep Sea, Ao’s memory is fractured into shards, and all she can cling to is remembering that she loved to sing. Her entire being is reduced to the affirmation of a single memory: her love of song. Here the story treads the limits of speculative fiction by suggesting that consciousness is reducible to a single memory.

While it may be a step too far for some, it does resonate with ideas about the relation of self to memory. One of the core tenets in Daoist thinking is forgetfulness. More than remembering, forgetfulness is seen as a path to spirituality in Daoism, since it is a process of stripping away the outside to access interiority. Deep Sea Aria reverses this idea. By tying Ao’s existence to a single shard of memory, her rebirth in Deep Sea is a process of forging connections, of creating relations of exteriority–new mnemonic resonances. As she slowly pieces together memories, her voice returns, and so to does her desire to socialize and connect. She becomes a threat to the technocracy, and her choice to sing publicly becomes an act of resistance. She spends her last three days giving underground concerts for the inhabitants of Deep Sea. Each song, each monologue, risks her being “deleted” by the state authorities, until in the end she is deleted.

Ao’s story arc is a poetic inversion of another well-known tale: Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid. The fairy tale surfaces repeatedly in the performance. Like the Mermaid, Ao sacrifices her voice and body for a dream of belonging. But unlike the mermaid, Ao finds rebirth in the very act of refusal. She reclaims her voice not to win love, acceptance, or recognition, but to affirm the meaning of existence in the face of crushing death. Her final statement, “I am happy to have been born” is a simple line made profound by its long, painful road.

The fact that the second world in Deep Sea Aria is titled “Archive,” tempts me to read the project as a Christian metaphor: Ao’s death as rebirth, Ao’s archive as resurrection. In this sense, while Deep Sea Aria still fits the posthuman narrative of life beyond finitude, where it differs from other fables are the reversals by which it gets there–a form of affirmative dialectics.

Ultimately, Deep Sea Aria asks what would remain of us if we became data. Ao’s upload to Deep Sea dramatizes the impossible choices of digital selfhood: what to keep, what to forget, whether consciousness is possible without a body, whether memories can be reassembled, and whether digital being is possible without a master overseer. Her longing to retain only her love of music becomes the thread that reweaves her fractured identity. In so doing, Deep Sea Aria explores grief as a type of code: stored, erased, rewritten.

Singing through grief

In the Deep Sea city, creativity is criminalized. Art is not just illegal, it is a danger to existence. Ao’s act of singing becomes a subversive gesture that brings to mind crackdowns of political protests in authoritarian regimes across the globe today. In one of her final speeches, Ao describes a mass protest in Deep Sea, in which artists painted the city in vivid colors, played strange instruments, and vanished as the bureaucratic authorities deleted them. Art is thus positioned as the last bastion between being and oblivion. This is VR performance as digital samizdat, a paradoxical call (but a real call) for freedom embedded in code.

Ao’s monologues are meditations on abandonment, trauma, and the slow erosion of the self. Her relationships, broken family ties, a vanished friend, the voice she almost loses, draw a map of disconnection. But her songs, fragile and glitching, become her bridge to others. Indeed, Ao Mihanada’s vocal performance as the character Ao is marked by a quiet sincerity that suits the VR format. Her delivery ranges from whisper-soft monologue to trembling, discordant ballad, always maintaining a tone of emotional immediacy. The use of first-person address and gentle audience interaction through spoken and written direct address dissolves the boundary between character and participant.

The songs themselves are deeply personal, blending J-pop melancholia with theatrical lyricism. Lines such as “If I disappear like seafoam, will you remember me?” or “Let it [my death] be your rest, your quiet space, not a cure, just grace” read like lullabies for the digitally lost. Lullabies that don’t induce sleep but wake us to the vulnerability of connection.

The Deep Sea Project demonstrates the possibilities of VR for new spatial-temporal modes of storytelling. By distributing voice, memory, and song across navigable worlds, Studio Aki has created a work that is as much an experience as a meditation on how narrative forms fit the expressive needs of our times. I think we are gradually moving away from the spectacle of immersion, to grappling with new modes of movement, listening, and being for the digital ghosts we may one day become.

The Deep Sea Aria VRChat public worlds are open until July 31 2025. To access them, download VRChat, create a free account, then search for “深海のアリア-Archive.” Here is the VRChat world link (Note: you must be logged in to access it.)