I want to share a few thoughts on a VR performance I saw recently called: Soultopia. It was created by Saeborg, an artist whose performances often use latex suits and large latex inflatables in the form of farm animals. Saeborg’s work is both playful and hard hitting in its critique of the normative roles that structure society.

Soultopia was part of the Theater Commons Tokyo, an annual performing arts festival based in Minato Ward, Tokyo, that produces and curates innovative performance work in Japan and beyond.

The VR platform for Soultopia was the ever popular VRChat, which hosts thousands of user created worlds, some of which are simply astonishing.

As I entered the lobby for Soultopia, I was told to put on a uniform black avatarusing a transformative mirror. The new skin immediately reminded me of larval masks, which are subjects that are still not fully formed.

The audience was then led through a portal into a bright new world, where we assembled on a galactic highway, surrounded by planets in a dizzying array of colors.

Portals and avatars are two of the main dynamics in VR worlds. The former enable participants to move through time and space almost instantaneously, and the latter allow for physical identity changes.

The first avatars we were given to play with were tapeworms. So here we were, lowly tapeworms on an intergalactic rainbow highway. We squirmed and played, some of us spoke in our very human voices. The humanity of the human voice, its timbre and cadence, but above all its idiosyncratic patterns, was the only thing anchoring this experience to a recognizable real.

Participants were encouraged to speak throughout the performance, either in our own languages (which in the case of the performance I saw, was predominantly Japanese), or in imagined languages that fit to the avatars we had changed into.

It seems to me that there is almost always a link to the phenomenological real in VR and digital experiences; a thread that maintains a signal between flesh and mesh. This is simply to do with the fact that all immersive digital experiences are (at this point at least) overlaid onto the human body through sensory equipment. There is no direct hardware-to-wetware feed, at least not for humans, that can bypass mediation.

Consequently, if VR avatars are part of an array of post-human paraphernalia that blurs the traditional nature-culture divide, nonetheless attached to its humanity through an umbilical cord of physicality. In the case of Soultopia it was voice. Participants used their headset mics to communicate.

Suddenly, a large red planetary body with a booming voice cut through the play. This morphological “big other,” an intrusion of radical alterity in what had been until that point, an immersive dive into the imaginary, beckoned us to another mirror and commanded us to “be reincarnated.” But it wasn’t so much a reincarnation as a relocation.

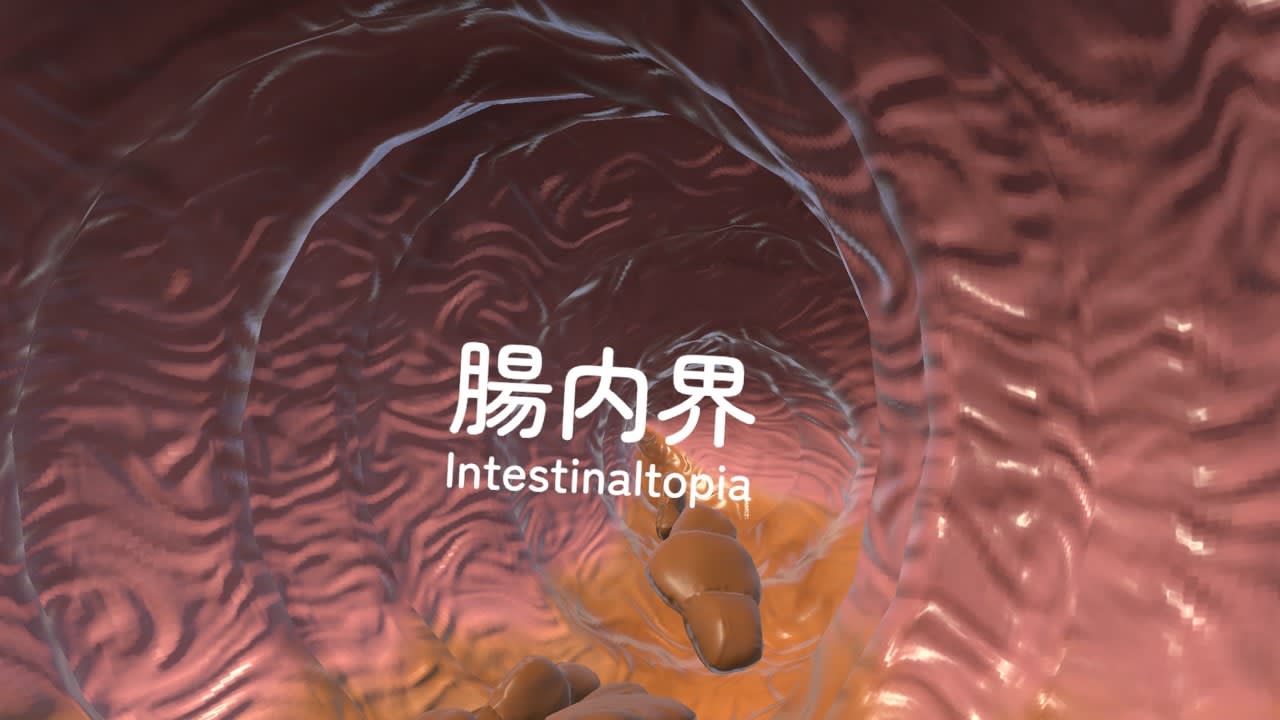

For a moment, the natural order of things was restored. We were inside an intestine, right where tapeworms belong. We could even manipulate the pieces of poo that lined the floor. From becoming other to belonging as other, such is the transformative allure of VR performances.

But no satisfaction is possible without the big other. And it returned in a new skin, encouraging us to speak as tapeworms. Participants grunted and snorted, flung poo at the speaking orb. Our collective commotion produced a bowel movement and a hole appeared. We were ejected into the cosmos, floating in our bemusement.

We landed back on the rainbow road. Our friendly orb invited us to change skins again. Sheep? Cow? Chicken? Pig? Those were the options in the mirror. Becoming farm animals placed us inside the frame of Saeborg’s previous works. Incidentally, Saeborg was one of the participants in the performance, playing the role of a facilitator, who helped the audience along.

From the galactic highway, we entered one last portal. Once more, we found our rightful place in this ethereal universe: a farm yard, complete with cabbage patch, mud pit and a big red barn. We roamed the fields, bathed in mud, before congregating at the barn. Before long, the great talking orb, now reincarnated as the sun, produced from its mouth, the farmer, which I believe (I may be wrong) was played by Saeborg.

The final act in this performance was somehow fitting: group therapy with the farmer. Fitting, in the sense that one of the themes under scrutiny in this work was identity. How we perceive the idea of “self” (ego,) and how the drives that bring self into being are intertwined, contradictory, often playful. The staging of our “selves” through the material attire that Saeborg allowed us to wear, brought multiple layers of introspection into what was otherwise a seemingly simple journey through stylised worlds.

One-by-one, participants lined up for quiet hugs with the farmer. This was an interesting moment of intimacy. The tactile embrace of a real world hug was replaced by an up-close inter-avatar moment of quiet. What, if at all, was transmitted in that instant, is hard to say without addressing each participant personally. But this simple gesture is another example of a cultural nexus in VR performance. What does this mean?

There are moments in VR performance works, where something seemingly mundane, such as a hug, or the exchange of an object, or the use of voice, takes on a different semiotic signature, attached to its real-world counterpart, but completely other inside the new coordinates or potentiality of its digital makeup.

As the euphoria began to wane we were lifted into the clouds, coming to rest in clinical white nothingness.

So what to make of Soultopia? In one sense, it was a promenade through Saeborg’s synaesthetic satirical worlds, in VR form. The use of avatars and portals, the overemphasis on plasticity in the various worlds we traversed, and the importance of colour codes, offered a transmodal experience across identities, languages, and forms, that harnessed elements of the multi-sensory potential of VR.

In another sense, it felt a bit like a mapping exercise, partly of the different properties that constitute VR worlds, partly of new terrain connecting performance and psychoanalysis. I hope Saeborg and Theater Commons Tokyo will continue this work. It felt like the beginning of new ground.

As I removed my headset and slipped back into my everyday me, I was left with some questions. Was I really “there”? What was that “there” and who was that “me”? Who were those other tapeworms? Were they standing, like I was, in the middle of a room, having left room time, home time, street time, to continue moving at its usual pace, while they secretly enjoyed this “elsewhere”?