Under a yellow crescent moon, Sakutaro, a lone samurai, lunges at a demon named Oboro, their katanas clash in a melee of steel. The battle is underscored by the vibrant clang of a shamisen. This is the opening to Koken No Tsuki (Moon of the Lone Sword), a live anime VR theatre production written by Kusano Satsuki (草野冴月), founding member of the Horizon Theatre Unit, designed by Ere (エレ), and directed by Meadow (めどう) at the Mashiro Shogekijyo in June 2025.

Mashiro, named after the Japanese word for “all-white,” a nod to the venue’s monochrome exterior, is a 50-seat virtual shogekijyo (little theater) that runs on the social VR app, VRChat. Operated by Meadow, a Japanese VR actor and director, Mashiro offers a diverse program including live theatre, dance, role-playing games, and comedy improvisation. The venue also helps newcomers develop original performance work tailored to the VR medium. Omnibus Performance Vol. 1, an anthology of four short Japanese VR plays produced in February earlier this year, is a good example of Mashiro’s dynamism and ingenuity in the Japanese VR theatre space.

Koken No Tsuki is set in Kyoto in 1867, a year before the collapse of the Tokugawa shogunate and the rise of the Meiji government. Three years have passed since the Great Genji Fire, which was triggered by the Kinmon Incident [1], and which consumed large swathes of the city. This historic period of upheaval was marked by a deep ideological divide between pro-imperial nationalists known as ishin shishi and the shogunate forces, which included the shinsengumi swordsmen, a group of 200-strong samurai tasked with restoring public order in Kyoto, as well as the mimawarigumi, a militia of high-ranking samurai tasked with protecting the imperial palace.

The Story

The play begins outside the Katsuraya okiya [2] in Kyoto’s Shimabara pleasure quarter, where a string of attacks on geisha has left the community in fear. Yumihari, a young maiko in a floral kimono, steps into a spotlight and addresses the audience. In a lyrical testimony, she recalls the horrors of the Great Genji Fire. Her speech is cut short but returns mid-way through the play, where her remembrance is staged against a glowing backdrop of embers and crumbling architecture, with ghostly figures scurrying through the wreckage.

The narrative then shifts to Sakutaro, a youth who like Yumihari was orphaned by the fire. He encounters the demon Oboro, and despite their initial clash of swords, Oboro refrains from harming him. Surprised to learn that Sakutaro wants to master swordsmanship in order to end war, Oboro offers to train him. A fluid montage-style sequence ensues (enabled by VRChat’s capacity for instant world transitions) depicting master and apprentice sparring in rice fields, a mountain stream, and under a moonlit bridge. These stylized shifts convey the passage of time, but also the internal evolution of the protagonist from boy to young man.

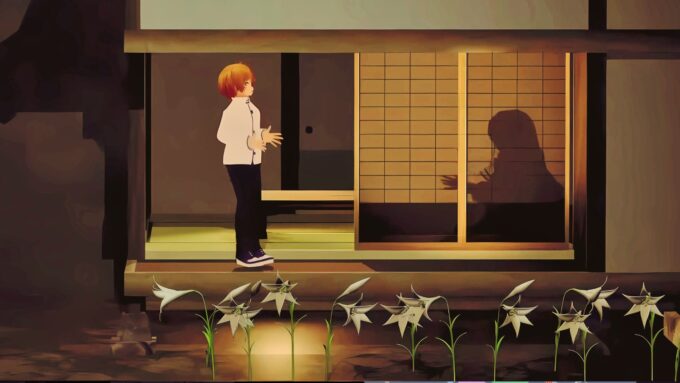

When the play returns to the present (1867), Sakutaro has become a samurai and joined the mimawarigumi militia. He encounters his childhood friend Yumihari, now older and resigned to her role in the okiya. Their reunion is interrupted by Katsuraya, the okiya’s owner, and shortly after by the reappearance of Oboro, who confronts and pins Katsuraya to the ground. As Sakutaro urges peace, Oboro refuses and the pair fight. Heavily wounded, Oboro flees the scene. This clash sets off a darker chain of revelations.

Katsuraya confronts Sakutaro and confesses that after Yumihari rejected his advances, he “scratched up a few courtesans as a warning.” He claims to be possessed by a demon, and it slowly becomes clear that Katsuraya framed Oboro as the perpetrator of the violent crimes so that Sakuataro would slay Oboro, allowing Katsuraya to restore peace, and thereby win Yumihari’s approval. Boasting of his plan’s success and confident in his ability to defeat Sakutaro, he fights the young samurai, only to be overpowered and killed when Sakutaro’s fellow militiaman enters the fray.

Sakutaro finds an ailing Oboro weeping under the bridge where they once trained. Oboro gives Sakutaro his katana, offering it to him as his “soul.” Oboro discloses that the “demons” that arose from the ruins of the city were born out of loneliness, and that Sakutaro must make it his mission to rid the city of all its demons. In the epilogue, Yumihari returns as narrator, hinting that peace has been restored and that Sakutaro has adopted the name “Oboro,” signaling his transformation into a more self-aware subject, one who carries both the memory of violence and the responsibility to transcend it.

Locating Oboro

Oboro’s identity remains deliberately unclear. Dramaturgically, Oboro’s role is cleverly constructed, because he/she/they hinges on the identities and motives of the three other characters, and is therefore a multi-layered symbol. On one level, Oboro can be read as the phantom of Sakutaro’s past. A literal representation of the grief and violence Sakutaro witnessed as a child during the Great Genji Fire. In this sense, Oboro is a therapeutic figure, returning as both adversary and teacher to compel Sakutaro to confront the unresolved pain of loss. Their training montage is a ritualized working-through of memory, guilt, and identity.

Sakutaro thus serves as both protagonist and transitional figure between old and new worlds. On the surface, he is a classic coming-of-age hero, a boy orphaned by disaster who trains under a mysterious master to become a samurai. But the deeper function of his character lies in his dual identification with both the violence of the past (as a member of the mimawarigumi, a force aligned with shogunate authority) and the possibility of moral transformation as Oboro’s protégé, a demon who paradoxically trains him to end war.

Another way of looking at Oboro is as a projection of Yumihari’s latent desire for retribution against violence. Oboro’s avatar has a black face with two horns that protrude from its forehead, which evokes the hannya (般若) demon mask from noh theatre. The hannya mask represents a female demon in the noh tradition, and is characterized by furrowed eyebrows and a wide-open mouth expressing both sadness and rage. The three basic colours of hannya masks are white, red, and black. Each one represents a different rank and social standing. The kuro-hannya (黒般若) mask is associated with a mountain mad woman.

If read as a manifestation of Yumihari’s rage, Oboro is a surrogate avenger, giving form to what Yumihari cannot openly express. Yumihari occupies a marginal position within the play, she is the first voice the audience hears and the last, yet she has no agency over the unfolding events. Her role reflects the historical and ongoing erasure of women’s voices in violent conflict. Not only is she a passive witness to the turmoil, but she also has to bear its emotional and physical costs—as a maiko, her body is already commodified and silenced.

If Oboro is Yumihari’s projection, then he is a transgressive agent, who breaks the binary between masculine action and feminine passivity. His disappearance at the end, and the revelation that Sakutaro has taken on his name, suggests a transference of that spectral agency into the body of a reformed and pluralistic subject (Sakutaro-Oboro-Yumihari), one capable of wielding justice not as vengeance, or as tradition, but as responsibility.

The Confession of Katsuraya

In the play’s climactic scene outside the okiya, Katsuraya, who is possessed by a demon, confronts Sakutaro and confesses that he enjoys inflicting pain, fear and anger in humans. This is delivered as a valedictory speech to Sakutaro, because the possessed Katsuraya believes he has achieved his aim of tricking Sakutaro to kill Oboro, and that he can now finally defeat Sakutaro too. But Sakutaro with the help of a fellow mimawarigumi swordsman proves to be too powerful.

Was Katsuraya’s admission of pleasure in violence simply a provocation? Or could it also be read as an admission of a psychological state? His self-proclaimed jouissance in violence turns him into a grotesque exaggeration of male authority in crisis, a patriarchal figure whose power has curdled into sadism. In this sense, more than Oboro or Sakutaro, Katsuraya is the implosion of feudal male subjectivity under the pressure of shifting power structures. He is no longer a stable individual, but a fragmentary echo of a collapsing order.

At the same time, if katsuraya is possessed by another demon, and following Oboro’s final speech, the demons at large in Kyoto are symbolic of “loneliness,” which is a form of lack—lack of meaningful relationships; lack of agency in a social space; lack of validation in being—then, like Yumihari and Sakutaro, he is dealing with the trauma of conflict, but its expression has taken a regressive form.

Parallels with Noda Hideki’s Red Demon

In addition to the connection of Oboro’s avatar design to the hannya mask in noh theatre, elements of the demonic figures in Koken No Tsuki are reminiscent of the play Red Demon by Noda Hideki. The play premiered in Tokyo in 1996 and went on to find success in numerous localized versions around the world, including an English version at the Soho Theatre in London in 2003.

Both Red Demon and Koken No Tsuki use the demonic other for exploring social exclusion, trauma, and the construction of otherness in times of upheaval. In both plays, the demon is not purely malevolent, but rather an ambiguous, liminal figure, feared and misunderstood. Noda’s Red Demon revolves around a foreign, red-skinned being who washes up on the shore of a closed-off island society. The locals immediately label him a threat, unable to comprehend his language or motives. Though he never speaks intelligibly, the Red Demon’s actions reveal compassion and vulnerability, especially through his bond with a girl named Ago.

Similarly, in Koken No Tsuki, Oboro is introduced in the opening vignette as a fearsome entity engaged in swordplay, but quickly subverts expectations: he refuses to harm Sakutaro, offers mentorship, and weeps by the bridge at the end of the play. He, too, is an outsider figure, associated with destruction but ultimately serving as a conduit for healing and insight. Both characters are scapegoated and misunderstood, embodying the fear of the unfamiliar or uncanny in communities grappling with collapse or radical change.

Live Anime Theatre: Form and Aesthetics

Koken No Tsuki blurs the boundaries between theatre, animation, and film, making it difficult to locate the performance within a single disciplinary frame. The structural conventions of theatre (liveness, stage, and audience) collide with the compositional strategies of cinema, (montage, dynamic soundtracking, and spatial editing). Layered on top of this is the stylized avatar and set design drawn from anime, producing a hybrid form that might best be described as live anime theatre. This fusion is not without precedent: commercial stage adaptations of anime, such as Live Spectacle Naruto (2016) and My Hero Academia The “Ultra” (2019) produced in Tokyo and Osaka by Live Viewing Japan, or My Neighbor Totoro (2022) by the Royal Shakespeare Company at the Barbican Centre in London, have explored similar territory, but all within a “2.5D” frame. These performances bridge the gap between the two-dimensional world of the source material (manga and anime) and the three-dimensional reality of the stage.

However, where Koken No Tsuki differs is in its use of VR as the compositional and experiential medium of the performance. Its 3D graphic architecture is not simply a frame or a backdrop, but an extension of the play’s aesthetic and dramaturgical logic. As I mentioned earlier, the production opened with a short ten-second swordfight that introduced the narrative and established the production’s core stylistic vocabulary: a blend of jidaigeki theatricality and kinetic anime visuals. The use of short, tightly composed vignettes recurred throughout the performance, enabling Koken No Tsuki to exploit a montage-like rhythm that VRChat makes possible.

At the same time, it is because of the “gaps” (or asynchronicity), in this layering of media that I became aware of a shift in my attention. While I found the plot and mixed-media effects engaging, I was also intrigued by the details of character design: the sway of a kimono sleeve, the fall of digital hair, the spill over of light from the glowing embers in the scene describing the fire in Kyoto. This detail produced a degree of detachment, a type of alienation effect. The avatars were lifelike but not alive; they moved with precision but not gravity. Rather than immersing the audience in illusion, the VR aesthetic constantly reminds me of its own constructedness. The result is a layered performance mode in which presence is always mediated, stylized, and suspended between registers.

At this stage of technological development, the aspiration for a seamless merger between real-world corporeality and virtual embodiment remains out of reach. Latency is hard to reconcile. But this is not necessarily a limitation. As with the visible puppeteers of bunraku or the mask work in Julie Taymor’s The Lion King, VR performance makes its gaps visible, between avatar and actor, world and spectator, sound and motion. These gaps are not necessarily errors to be overcome, but aesthetic opportunities, spaces in which new modes of spectatorship emerge, oriented not toward immersion but critical engagement. In Koken No Tsuki, this intermedial tension became part of the substance of the performance.

Final Thoughts

Drawing on elements of noh, jidaigeki, the shogekijo spirit of experimentation, and anime style, Koken No Tsuki is an interesting hybrid of pre- and post-digital pop culture. Its use of avatars, montage, and VR spatiality reflects a conscious negotiation between tradition and new technological creative possibilities. Through this negotiation, the play reconfigures both form and content, showing how the virtual stage can become a site for reckoning with historical trauma, social hierarchy, and the elusive specter of justice.

Notes

[1] The Kinmon incident was a rebellion by the Choshu clan against the Tokugawa shogunate that took place on 20 August 1864, near the Imperial Palace in Kyoto. The Choshu forces attempted to take control of Kyoto and the Imperial Palace but were ultimately defeated. One of the unintended consequences of the battle was that the rebels set fire to the Takatsukasa family residence, which then spread across the city, extending from east of the Kamo River to Teramachi, and even threatening the Imperial Palace and Nijō Castle.

[2] An okiya is the lodging house/drinking establishment to which a maiko or geisha is affiliated during her career as a geisha. The okiya is typically run by the “mother” (okā-san) of the house, who handles a geisha’s engagements, the development of her skills, and funds her training through a particular teahouse.