Discordance, is an intermedial VR dance performance by Unwired Dance Theatre, directed and choreographed by Clemence Debaig, which premiered at London’s Rich Mix Theatre as part of OOTFest in November 2022. The show under review here was part of the XR Live Performance Exhibition 2023.

In Discordance, the audience follows a blue avatar through multiple landscapes, including a cherry-coloured mountain range, a machine-run dystopia, scrappy grasslands where TV sets seem to mushroom out of the ground, and a forbidding cave that gives way to a clearing surrounded by colourful trees.

As the piece progresses, it becomes apparent that the blue avatar is a multiplicity of beings, appearing at times in double and even quadruple form, before merging back into one. Its others have different colours, but share the same basic polygon form. Other avatars appear in the work, but since they share the same form, it is difficult to distinguish individual character traits. This ambiguity of persona is one of the main conceits in the piece and I will return to it later on. For the remainder of this review, I will refer to the blue avatar as “they” in recognition of this multiplicity.

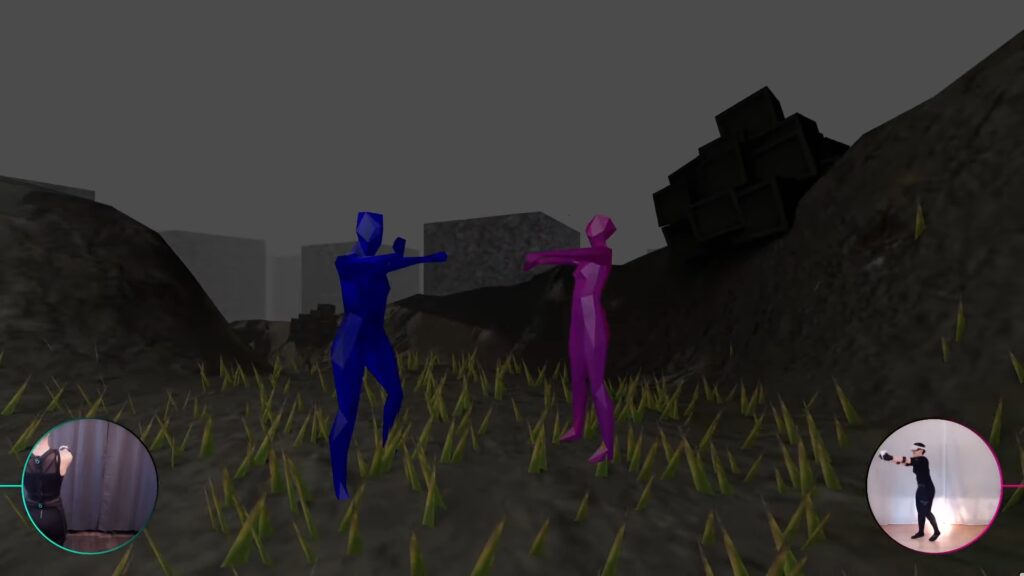

The blue avatar and its others are were animated in real time by Lena Adele Wolfe in New York and Livia Massarelli in London. The dancers were present both in their avatars’ movements and as themselves (wearing VR headsets and tracking straps) on screen in two small circular video feeds.

As the blue avatar progressed through the landscapes, they searched for a place to belong: perhaps a home, a community, or a partner(s). Several opportunities arose along the way. Early on, for example, they met a friend (a purple avatar) and tried joining a dance troupe that was practicing in front of a large mirror. They were quickly distracted, however, by the arrival of grey machines. Soon, the soft cherry landscape dissolved into a hypermechanized zone, where they tried dancing with robot workers in a sprawling open air factory. Moving in time to the mechanical beats created by musical director, Christina Karpdini, they were met with apathy and neglect.

They moved on to the outskirts of the industrial sprawl, reaching a grassy road, where they shared a series of brief encounters with other avatars. Staged as duet dances, these impromptu rendez-vous varied in expression from slow and sensual dances of intimacy to frenetic movements suggesting discord and alienation. Were these encounters with strangers or were these strangers facets of the avatar meeting themselves? A the final egancounter in this sequence took place in a cave. The music shifted to a grinding, menacing tone, and the blue avatar was suddenly in the grip of a shadowy figure. The ominous red eyes of this assailant pierced their blue body on each blow, leaving them writhing in pain on the cave floor.

Wearily, they picked themselves up and a clearing emerged. Tree-like forms, in blue, yellow, pink and turquoise colours sprang from the ground, and the avatar split into four figures, each with a colour matching the trees. Their ensuing circle dance was one of the moments in Discordance, in which some of the audience participants were able to interact with the performers. The sequence was set to an upbeat track interspersed with recorded voices of people talking about personal experiences of integration and alienation. As the voices receded, the avatar’s four bodies merged into one and brought the performance to a close.

One of the many interesting aspects in Discordance was the division of the audience into three tiers, each with a different ticket price. The first tier accessed the performance via a livestream video feed. The video was filmed in real time by an in-performance camera operator. The second tier, which is the one I opted for, consisted of “invisible participants” who viewed the show through their own VR headsets, and could cohabit with the performers in the VR world as silent and invisible avatars. Participants were able to move around the space freely and choose their own viewing angles.

The third tier, referred to as “active participants,” also accessed Discordance through VR headsets, but appeared as visible avatars and were able to interact with the dancers in the virtual world at given points. The final circle dance was one such moment. Their avatars, designed by Debaig, consisted of a torso, head and hands, and were much simpler in from than the blue avatar and its others.

While tiering of audiences is not uncommon in VR theatre and dance works, it is worth exploring its ramifications in the context of Discordance as it gives insight into the social structure at work within the piece, and within VR worlds in general. On one level, the tier system mimics the tiered economies of traditional proscenium theatres, in which audiences tend to pay a premium to sit in close proximity to actors on stage. Underlying the logic of that economy is the idea that the experience of co-presence is a desired form of objective social interaction. That proximity to the actor influences the reception of the performance to a higher degree of immersion. Audiences sitting at the peripheries of large auditoriums still often use binoculars in an attempt to reproduce something of that tele-proxemic effect. Near or far, however, there is still a substantial social boundary built into most real world theatre architectures. Live performances in VR extend the possibility of co-presence, by opening up the endogenous or subjective dynamics at work in social interactions, such that performers and audience members may experience synchronicity of attention, feeling and behaviour, however fleeting or momentary.

On another level, the distinction between visible and invisible participants reflects the primacy of appearance in virtual environments. While visibility is always a factor in social experience, in VR it becomes a principal axis through which identity and presence are communicated. In Discordance, even though the avatars were rendered in minimalist polygonal forms, essentially without facial features or personalised facial expressions, the act of being seen, of being acknowledged as present, still mattered. To exist in the space as an avatar was to participate in a social choreography of recognition.

The “active participant” tier took this one step further, offering a limited but significant opportunity for audiences to engage with performers. That said, from my “invisible” vantage point, it was difficult to discern exactly when and how these interactions took place. This perceptual gap raises questions about the dramaturgy of inclusion in VR spaces: who gets to be seen, who gets to touch the performance, and what remains opaque to others depending on their role?

In the machine-dominated zone of Discordance, the blue avatar split into two overlapping iterations of itself, one “solid” and one “translucent,” while the live video feeds of the dancers remained visible in their circular screen-edges, each performing in their respective real-world studios. This multilayered composition, two avatars in a shared virtual space, two bodies across oceans, revealed the contradictions embedded in proximity and intimacy. We can be close, even entangled, and yet also vastly apart. Discordance does not resolve this contradiction. Rather, it makes it visible.

The world-building of Discordance helped underscore these emotional and thematic tensions. In a sequence that transitioned from lush cherry blossoms to a charred industrial wasteland, the avatar danced through landscapes scarred by machinery and marked by loneliness. And yet, through all this, the avatar moved forward, not in triumph, but in solidarity. The final clearing, where the four coloured avatars joined the audience in a communal circle dance, did not offer resolution, but rather a moment of shared rhythm, a temporary alliance against disintegration.

Ultimately, Discordance is a work about fractured connection. Through its use of real-time VR performance, split embodiment, and audience stratification, it meditates on how we seek one another, how we mirror and miss each other, and how, even in dissonance, we might briefly harmonise. It is a choreography not of closure, but of co-presence: provisional, porous, and tender.

Direction, choreography, tech @clemencedebaig_art

Performed in London by @livia_massarelli

Performed in New York by @merlena19

Music: @christikarp

3D artist and worldbuilder: @joeibbettvfxartist

Dramaturgy: @brendanabradley

Technical support stage management system OnBoardXR: Michael Morran