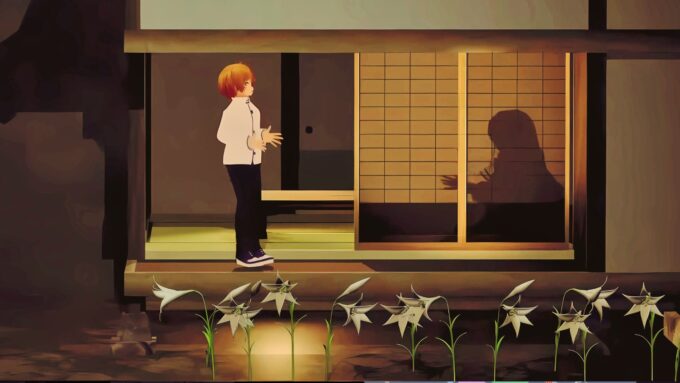

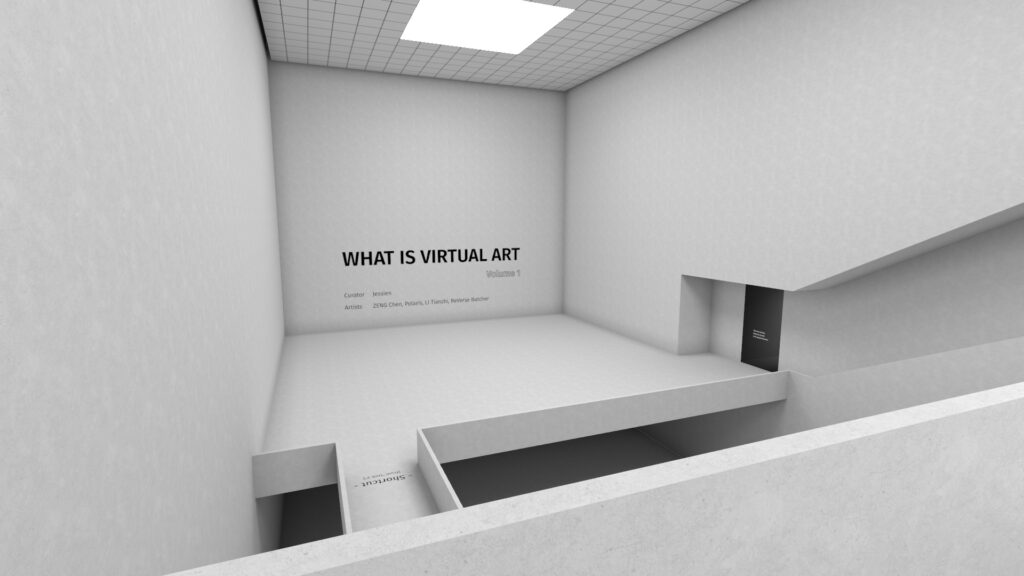

What Is Virtual Art – Volume 1 is an ambitious attempt to rethink the history of visual storytelling through immersive VR technology. Curated by VMoVA (Virtual Museum of Virtual Art), and presented as part of the Raindance Immersive Festival 2025, the exhibition features four artists, Zeng Chen, Polaris, Li Tianzhi, and ReVerse Butcher, each exploring how traditional concepts in the performing arts and plastic arts, such as shadow play, set design, pop-up books, and collage find new expressive potential and significance in VR.

Even before stepping into the exhibition, the framing question What is Virtual Art? acts as a provocation. The fact that this project is structured in volumes suggests the possibility of a sustained intervention into the very large question of what constitutes virtuality in the context of art today. It is provocative in that its ambitious scope means returning to a “grand narrative” approach to the discussion of art. This is perhaps inevitable given that virtuality has been central to art from its earliest manifestations. The paintings at Altamira and Lascaux were born out of darkness, inscribed on cave walls by firelight. These expressive lines were acts of revelation, partly about the reality of the world, and partly about the means of perceiving the reality of the world. Virtuality is the interplay between the world and its double, and is a key function in the process of abstraction.

What Is Virtual Art – Volume 1 (WIVA-v1 for short) recasts virtuality as a bridge or trajectory between artworks and their meaning: between object and subject. This trajectory is multifaceted; it is semiotic, spatial, temporal, sensorial, and meta-critical—since it draws attention to the boundaries of materiality that humans have ascribed to the status of artworks over millennia. This trajectory is also multidirectional, moving between past and present, while also opening new potentialities that digital 3D environments offer in terms of the creation, representation, and experience of art.

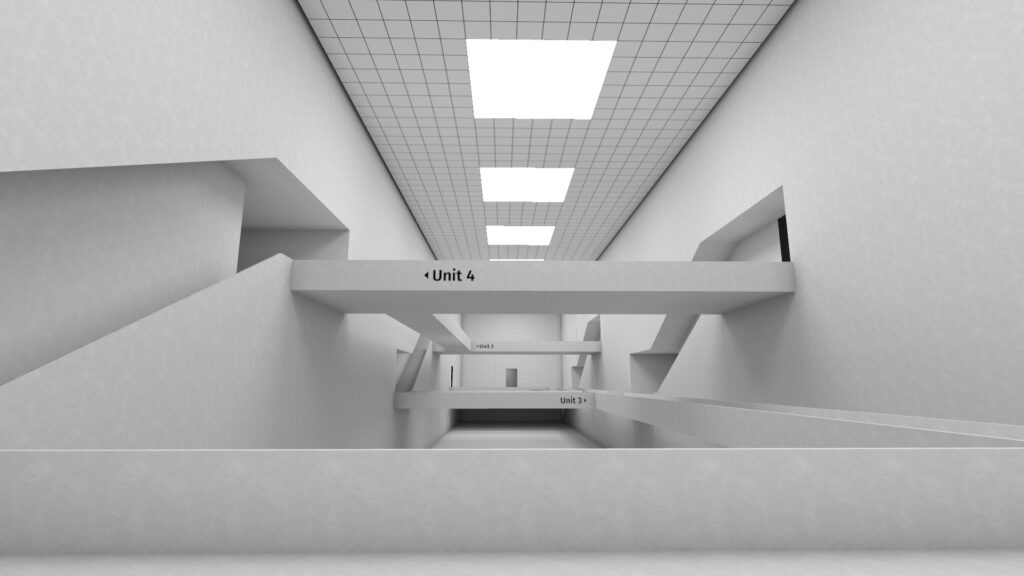

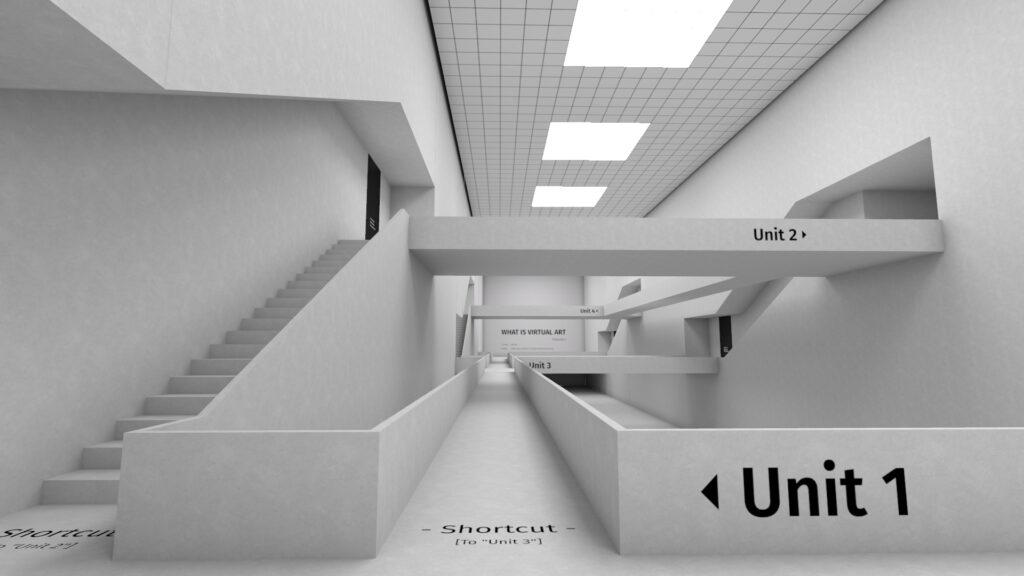

Where WIVA1 is at its best is in “showing doing.” Each exhibit gives a glimpse into the technical workings and cultural significance of scenographic art. Zeng Chen looks at animation and perception, Polaris tackles architectural perspective, Li Tianzhi focuses on 3D representation, and ReVerse Butcher explores sculptural form and virtual presence. The VR medium is particularly adept at turning these concepts into unique experiences, and WIVA-v1 is an astonishing feat in its seamless presentation of complexity. Where the exhibition falls somewhat flat, for me at least, is that the exhibits can feel overly didactic. And while didacticism is not negative per se, in the context of this light-grey, laboratory-styled VR gallery, there is a limit to show-and-tell before the desire for art’s capacity to rip out the guts of existence comes calling.

But perhaps that is also WIVA-v1’s point: that so long as humans do not subsist as data—even though our actions and behaviors are increasingly tracked and repackaged as data—then virtual art is ultimately a trajectory that returns us to the gristle and grime of our earthly world. WIVA-v1 is part technological sublime, part 3D modeling magic, part art history, and part creative innovation. Whether there is sufficient critical depth to fend off the fetish of spectacle that prowls around many aesthetic experiences in the metaverse, and whether the trajectory returns you differently than when you began, is for you to decide. Let me now move on to the four main exhibits.

Shadow Play: Zeng Chen’s “Tracing the Shadow”

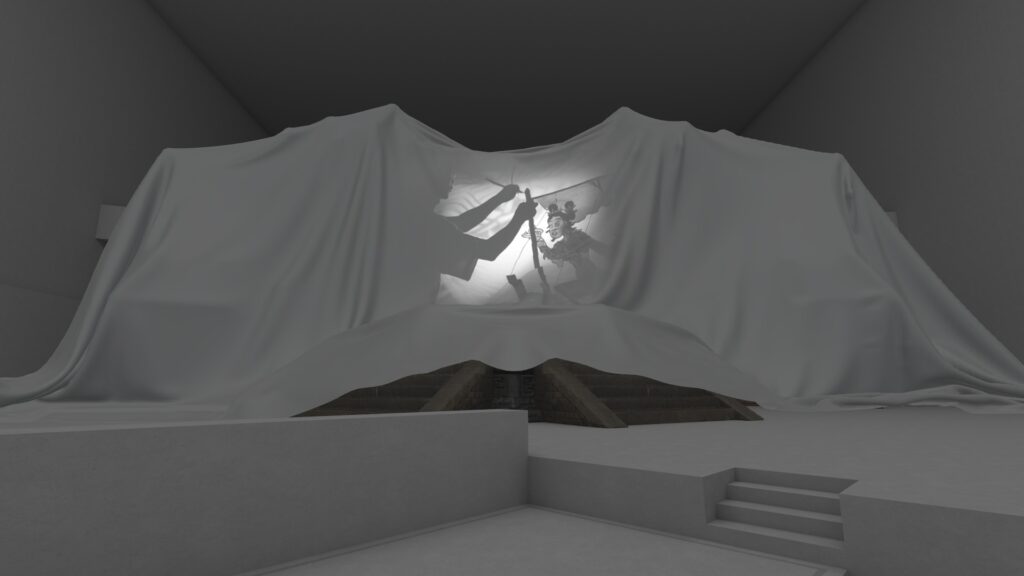

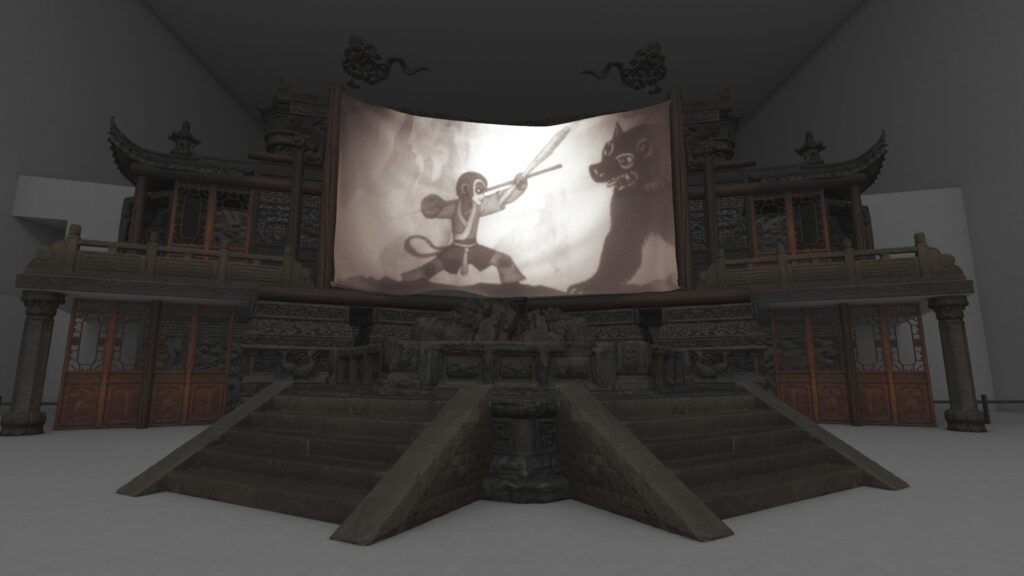

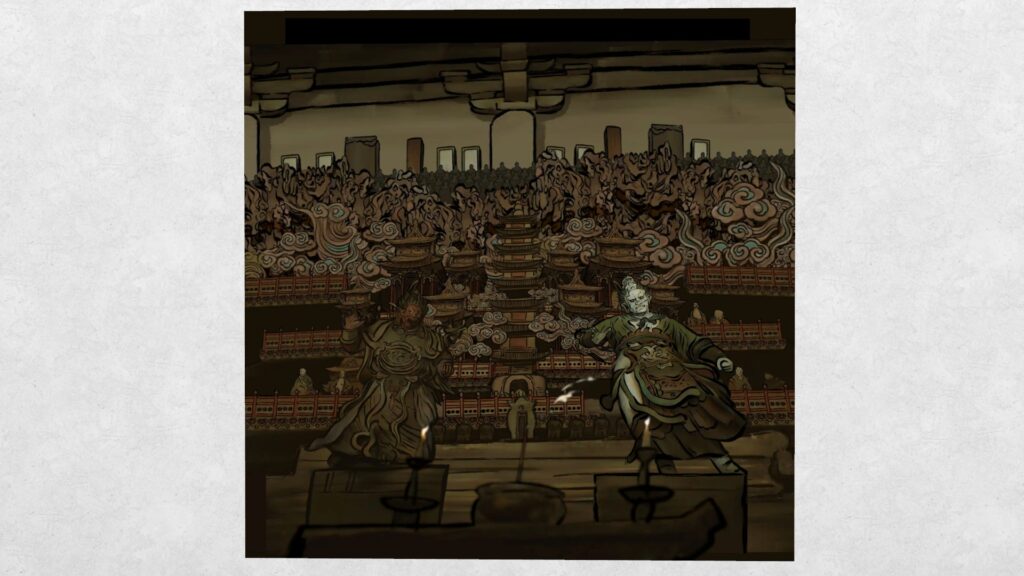

Zeng Chen’s installation is perhaps the exhibition’s most historically resonant piece. Recreating the Chinese shadow play tradition of the Song Dynasty, the artist deploys Unity’s real-time lighting engine to demonstrate the aesthetic and technical principles of this ancient medium. At first glance, it is simply an oversized puppet performance of Journey to the West, but the closer you look, the clearer the curatorial intent becomes: to underscore how illusion is constructed—both then and now.

Traditional shadow play required dozens of skilled artisans to orchestrate the play of puppets behind the screen; here, that labor is re-enacted through 3D assets and dynamic lighting. The layered shadows Zeng pays tribute to are preserved, though digitally, evoking what he calls the “hazy beauty” of imperfect projection. The piece also cleverly acknowledges the tension of scale: the virtual stage exaggerates proportions to enhance clarity while retaining the genre’s intimate feeling.

“Tracing the Shadow” looks back at the Chinese cultural heritage of shadow puppets to question if and how the puppet can produce aesthetic value in virtual worlds—where the mechanisms of puppetry are now largely concealed in code. The VR shadow puppet is “thrice abstracted” from reality; once as the human manipulation of an inert object, twice as the projection of that manipulation onto a cloth screen, and thrice as the screenification of that manipulation in 3D space. There is a certain melancholy feel to this scholarly explication of shadow play; it is an homage to a beautiful tradition, and a timely update to its coordinates in this age of virtuality, but also perhaps a goodbye to the childhood thrill of wondering “how does it all work?”

I suspect that part of what prompts us to wonder how a puppet works is context. The context of puppetry is the suspension of disbelief. We know the puppet is real, and we know its shadow is real, but we also know that the stage, screen, and auditorium are parts of a performative context that grants us access to the virtual dimension of the puppet and its shadow. In that dimension, the puppet can be an ancient king slaying a mythical beast. The possibility of reverse engineering the construction of this context is inscribed in the artifice of puppetry itself. In shifting the shadow play into a VR space, we are forced to contend with that third layer of abstraction, and its trajectory takes us beyond the traditional context of puppetry.

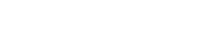

Theatrical Scenery: Polaris’s Accelerated Perspectives

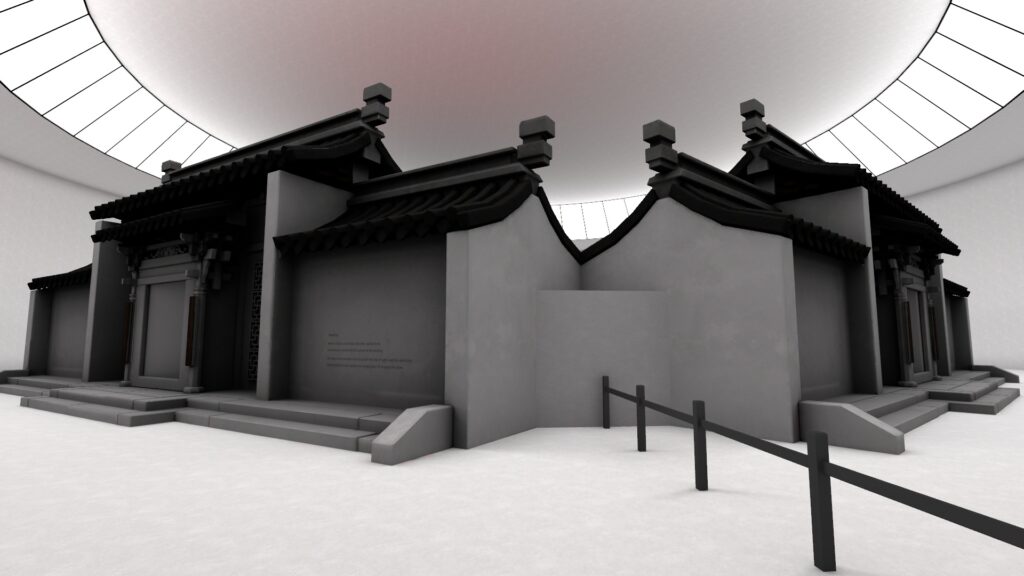

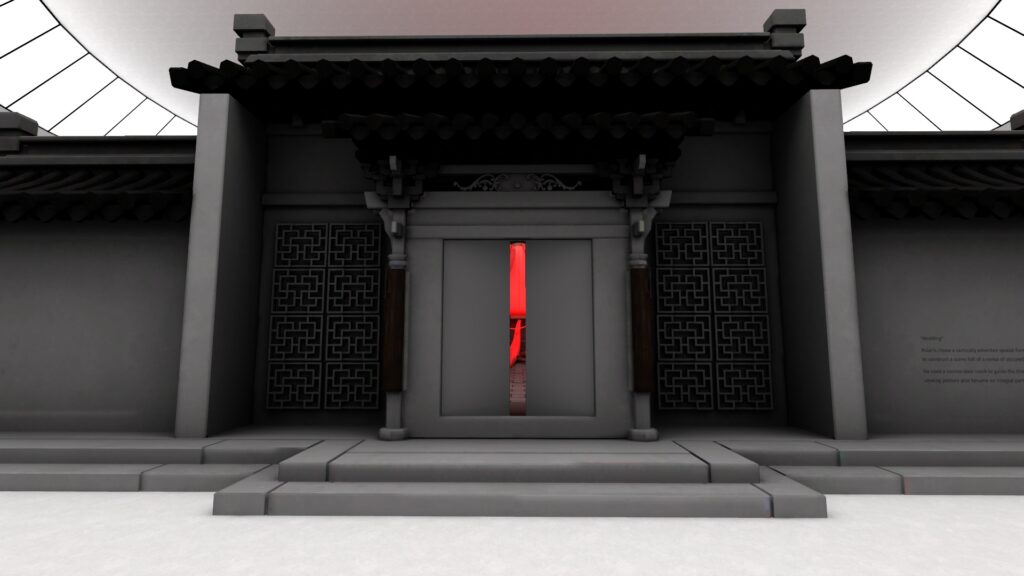

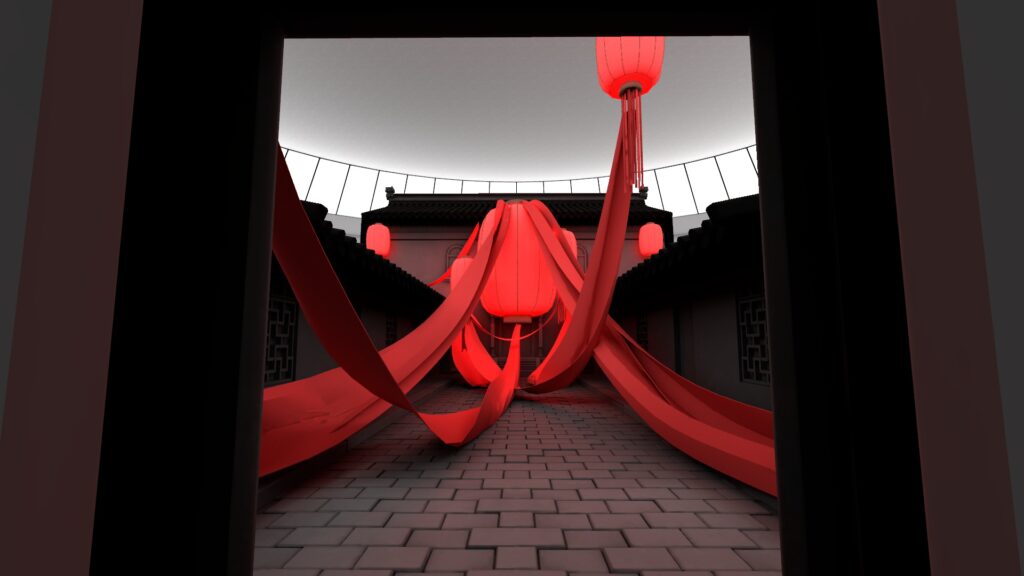

Polaris brings a contrasting sensibility to this show, bridging architecture, mathematics, and perspective. The center piece in his unit takes the form of a traditional Chinese house. Positioned outside the house, the audience is invited to explore its four “sides,” each of which contains a door that is slightly ajar, revealing a scene inside. The scenes are titled “Wedding,” “Family Photo,” “Fall,” and “Reveal.” The act of peeping brings the question of the viewer into the frame. How do we perceive objects, from what position, with what intention, and by whose design? This work reminds me of the famous wooden door in Marcel Duchamp’s last major piece “Étant donnés” (1966), with its famous peepholes that reveal a 3D world within.

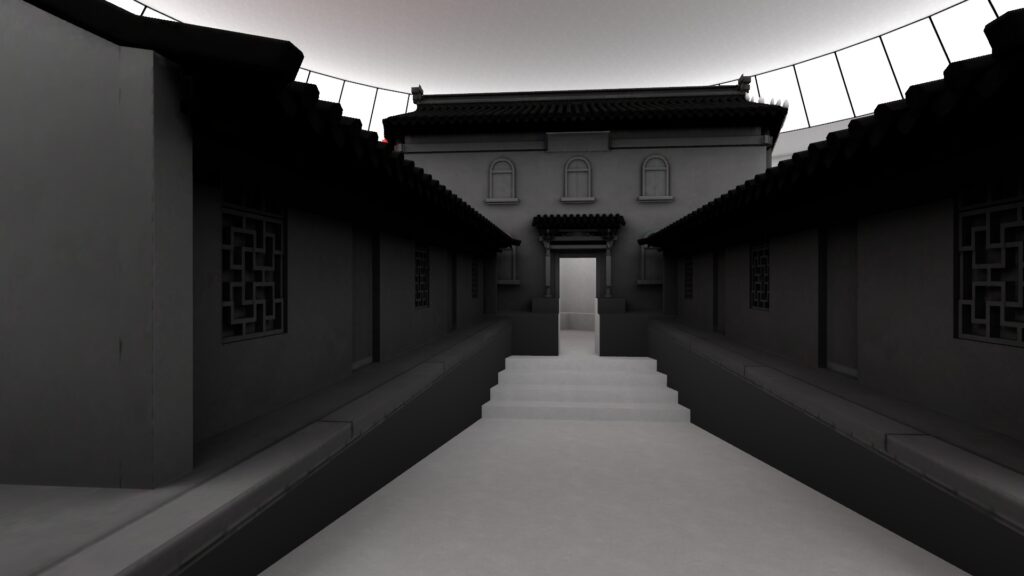

Polaris’s world plays with the theatricality of perspective and is a demonstration of the Renaissance concept of “accelerated perspective,” a technique (we are told) that was first pioneered by Baldassare Peruzzi, an Italian architect and painter active at the turn of the 16th century. Stepping inside the fourth scene “Reveal” felt like traversing a theatre model box that had come to life, complete with forced vanishing points that shift as you move. This spatial trickery transforms static compositions into dynamic, interactive dioramas. The interlocking dark and light zones in “Reveal” carry different perspective relationships, heightening the sense of impossible depth.

That Polaris is a graduate student in engineering underscores one of this exhibition’s core messages: VR as a medium invites cross-disciplinary creativity. The Raindance Immersive Festival program described Polaris’s work as “quietly disorienting,” and I think that captures the odd pleasure of feeling the floor tilt beneath your gaze without any physical motion at all.

Pop-Up Books: Li Tianzhi’s 3D Scrolls

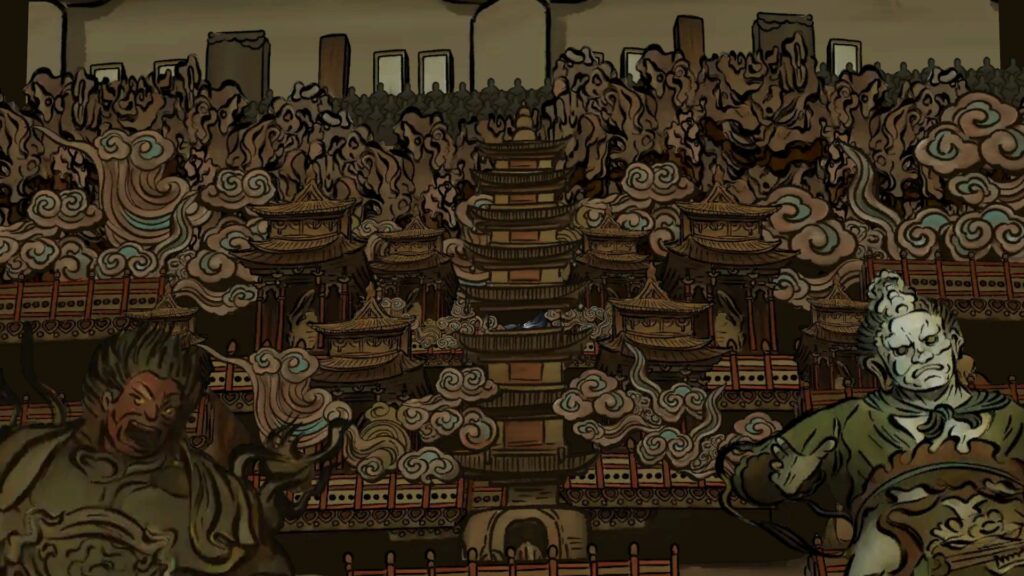

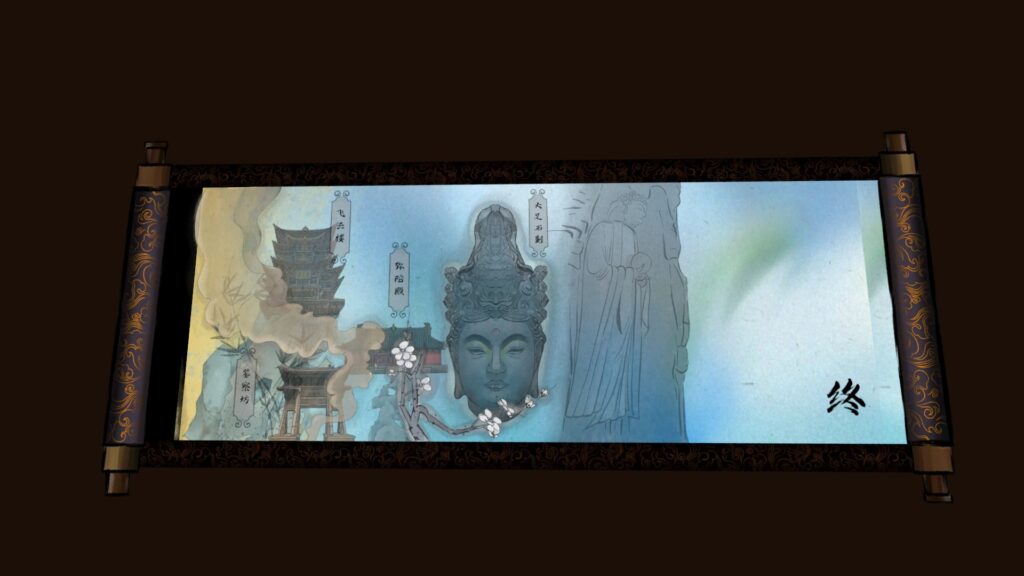

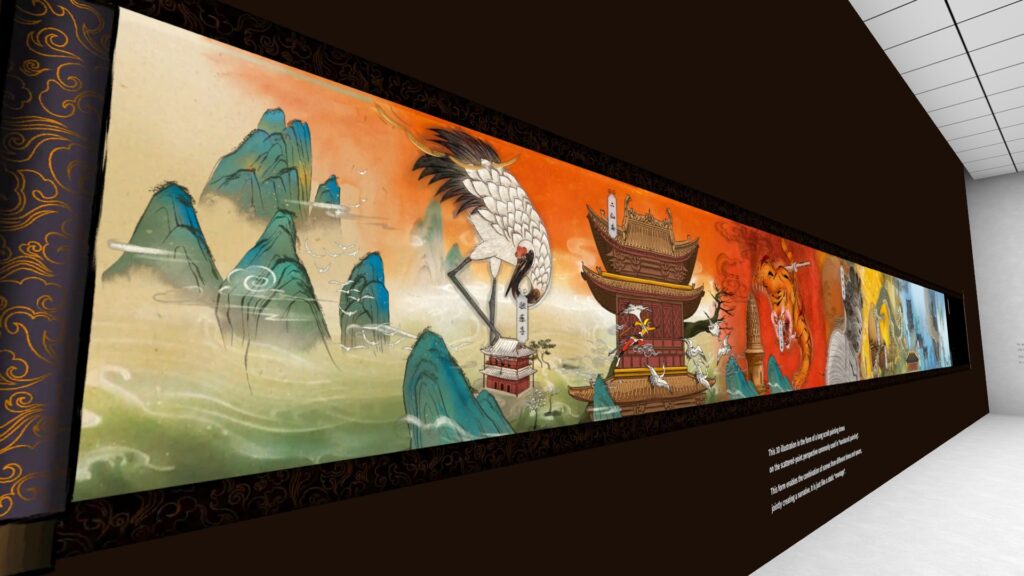

LI Tianzhi’s section bookends nicely with Polaris’s reflections on perspective, since it celebrates the intersection of illustration and architecture. The exhibit takes the audience through a series of layered 3D illustrations that take inspiration from tunnel books and handscroll paintings, reimagined here as immersive, perspectival vignettes.

In the prologue section of the exhibit, Tianzhi reproduces a tunnel book, a pop-up toy that creates depth through stacked layers. He reimagines the tunnel as a rotational world, evoking in one instance a planet in orbit. When rotated, this 3D structure generates an unexpected visual sequence, similar to zoetrope animations. This prologue suggests that depth is not only a function of our perception of distance, but also a function of movement. In his tunnel books, rotational motion becomes a narrative device, replacing the turning of a page or scroll with the turning of a world.

This exploration of depth continues in the main section of Tianzhi’s exhibit: the layered 3D vignettes. Seen from a distance, each scene appears as a 2D illustration of traditional Chinese literary and religious themes. As the viewer moves closer, the images reveal depth and shift onto a 3D plane. The highlight of this unit comes after viewing all the vignettes, where the audience is now fully immersed inside the illustrations and moves through them in sequence. This transformation in perspective, from 2D to 3D, and from external viewer to internal actor, draws attention to the compression of space, time, and narrative form in virtual worlds.

Traditional Chinese handscroll paintings are known for their scattered-point perspective, which allows multiple spatial and temporal moments to coexist on a single visual plane. Tianzhi translates this into digital form by using layered illustrations within a 3D space, effectively creating a static “montage.” The 3D scroll becomes a temporal architecture in which viewers scroll through time, space, and memory not by unrolling the painting but by shifting their perspective within a digitally constructed scene.

Collage: ReVerse Butcher’s “Circle Series”

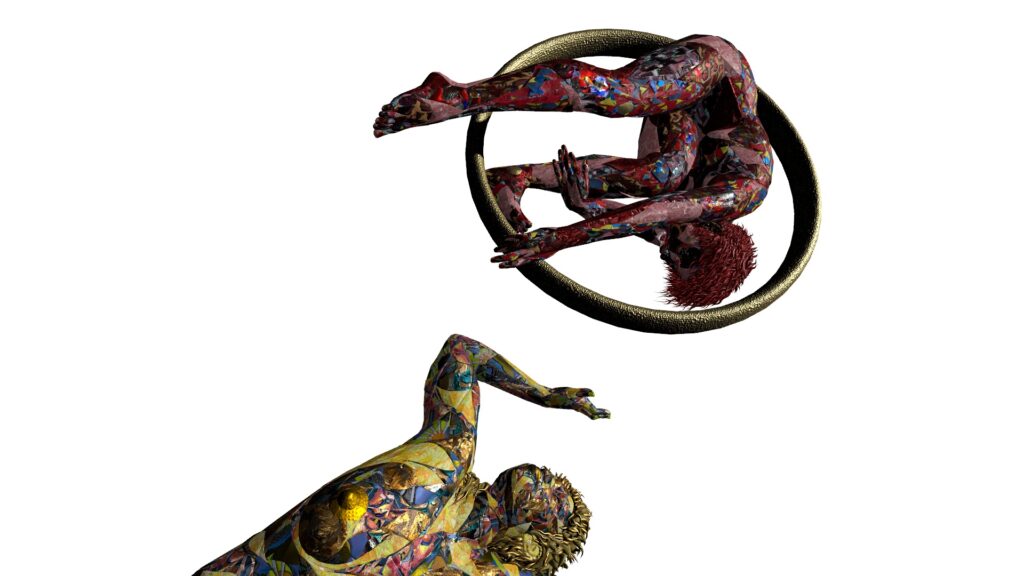

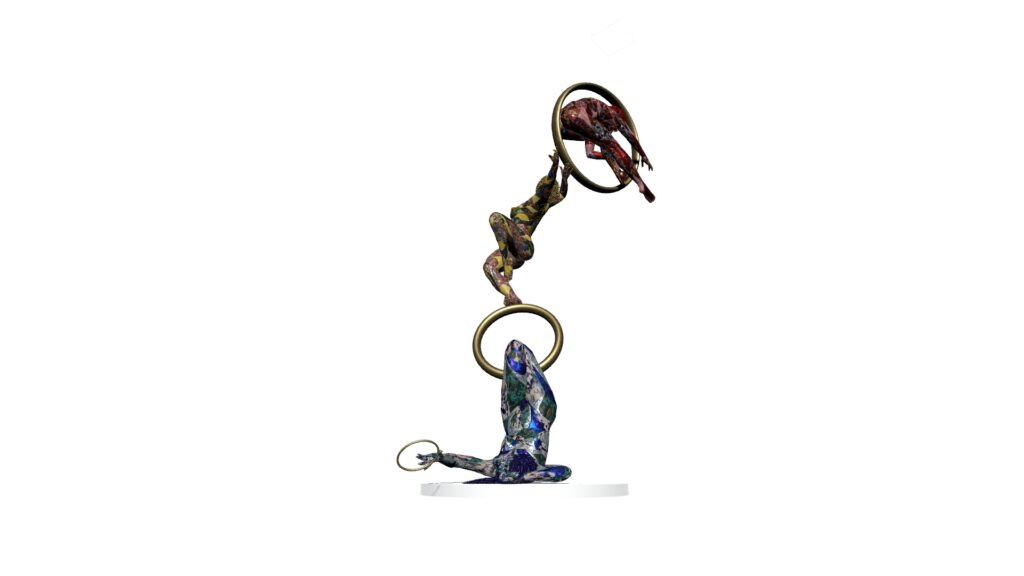

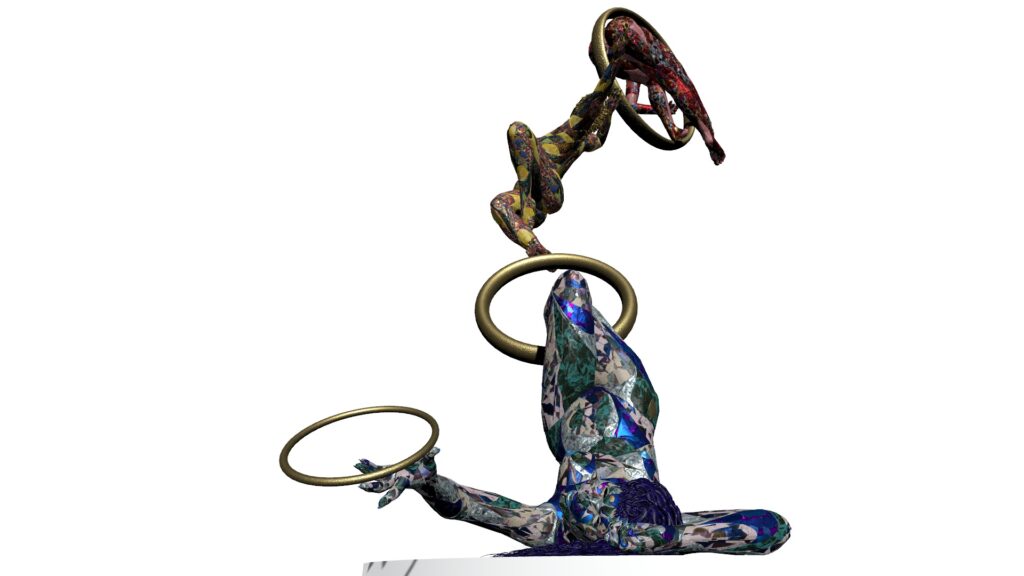

ReVerse Butcher’s contribution to WIVA-v1 draws on early 20th-century collage and her own long-running exploration of mixed media. The exhibit consists of a series of three large sculptures of female figures interacting with gold coloured aerial hoops. The audience encounters the figures in sequence, moving up through platforms which offer new perspectives on the sculptures as well as explanations of the creation process.

This series is the culmination of experimentation with form, moving from traditional paper materials, including old book pages, ink, acrylic, to digital illustrations, and finally to the creation of large-scale 3D versions of the digital prints using Open Brush in VR. The sculptures are constructed in what Butcher describes as material “groups.” Sections of material that overlap in collage form to create the sculpture. The different groups appear as you ascend the installation structure, and form a complex “skin.”

The use of collage is an interesting choice in the context of VR. The textures of layered materials, which include decayed books and water-stained paper takes on a different sensory feel in VR than it might in a real-world installation. I found myself less aware of the “seams” between materials, and more involved in the environmental scale of the work. The three women float in a boundless white space. There are no gallery walls to delineate the experience. These women seem to have always been there.

The materiality of the sculptures only came into view for me at the end of the installation, where I was able to drop down from the virtual scaffolding to the base of the first figure. Moving closer to inspect the material, I found myself inside the sculpture, in a completely different world: a disorienting entanglement of colours, textures and forms. This interior space (cf. third photo below) reminded me of Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of “the body without organs.” The body without organs (BwO) represents a body’s potentiality, its capacity for change and becoming, before it has been shaped and organized by external forces or internal structures. One of the many examples Deleuze and Guattari give of a BwO in A Thousand Plateaus is the Earth: “The Earth is a body without organs. This body without organs is permeated by unformed, unstable matters, by flows in all directions, by free intensities or nomadic singularities, by mad or transitory particles” (p. 40).

Perhaps the BwO is one way of thinking about what virtuality can be in the context of VR: unstable matter that flows in all directions. I was intrigued by Butcher’s parting note at the end of the exhibit, in which the artist explains why she chose to stage three women: “Three is outside the binary, it’s more than two, and it’s the best way to balance everything out. One is alone; two is a fight; three is a conversation.” It’s an interesting mental exercise to consider balance as something formed of three parts. It suggests, again in the direction of Deleuze and Guattari, that balance is unstable, a becoming.

Butcher’s sculptures blur the line between static artifact and living performance. They invite the audience to reimagine embodiment, gender, and form outside of fixed binaries. They feel hand-made, but also algorithmic, and they confront us with the material and emotional residues of being human. Accompanied by a haunting soundtrack composed in Virtuoso VR, these figures leave a lingering presence, and were, for me, the highlight of WIVA-v1.

Final thoughts

What Is Virtual Art – Volume 1 is less an answer to the question it poses than a demonstration of how varied those answers can be. Each artist excavates a different tradition, repurposing it through digital tools without erasing its history. WIVA-v1 is a bold start to an important intervention in media archaeology. The scale of this undertaking, both in terms of its core concept, and world design, is proof that curatorial ambition can thrive in platforms like VRChat, and that immersive art has a lot to say about the state of the world. At a time when virtual art risks becoming synonymous with algorithmic novelty (particularly in the crypto space), this exhibition reasserts that technology is only as meaningful as the stories it helps us tell. If you enter WIVA-v1, which I highly recommend you do, expect not just to look, but to be looked back at, and to be reminded that virtual worlds are as much mirrors as they are screens.

How to access this exhibition: 1. Download VRChat on your PC. 2. Create a free account and login. 3. In the “Worlds” tab search for “What is Virtual Art.” 4. Launch the world.